The War of 1812

The war of 1812 was the first test of the militia system and the ability of the regular Army to expand to meet the needs of the nation during a major war. While this war was a major effort for the United States, Napoleon, and therefore, France was the main focus of the opponent in the war, which was fortunate for the United States.

The war of 1812 was the first test of the militia system and the ability of the regular Army to expand to meet the needs of the nation during a major war. While this war was a major effort for the United States, Napoleon, and therefore, France was the main focus of the opponent in the war, which was fortunate for the United States.

The regular Army in 1808 had been expanded from 2 regiments to 7 of infantry, and one regiment each of riflemen, light artillery and light dragoons. This measure was taken in part due to the failure of the states to see to the arming and training of the militia. To help rectify this situation, $200,000 was appropriated by Congress to arm and equip state militias. In late 1811, an additional 13 regimets of regulars were authorized, presumably to be recruited from militia units. By the time war was declared, the regulars numbered some 7000 men, and West Point had produced 71 officers. The bulk of the Army would have to be made up from militia.

The turnout of the militia was unsatisfactory. States such as Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire and Vermont refused to call forth their militias, as no invasion of the United States had occured. The plan to raise the national army on the model of the Continental Army was failing, and in January of 1813, Congress increased the number of regular army infantry regiments to 44, intending to have them filled by militia units signing on for a one year term of service.

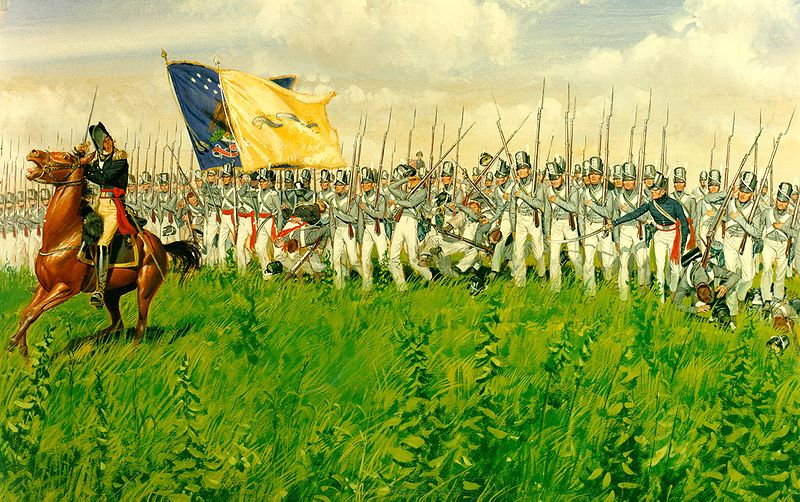

By 1814, the steps taken to correct the disasters of previous years were starting to take effect. The Secretary of War had been replaced, and men who had proven themselves were promoted into a new group of generals. One of these new generals was Winfield Scott, who had distinguished himself while commainding the 2nd Artillery, and was given command of the Erie expedition. Scott's army consisted of two brigades of regulars (9th, 11th, 21st, 22nd, 23rd, and 25th Infantry) being among the newly formed regulars, some men had less than 4 months service when Scott arrived, and a brigade of militia, consisting of regiments from New York and Pannsylvania. Scott went to work instructing his army via the Von Steuben method - he personally taught the regimental officers as a drill sergeant, who then taught the company officers, and so forth. The battles faught by Scott, Chippawa and Lundy's Lane were the first time the US Army met and defeated regulars of the opposing army. Chippawa is famous in Army lore, as Scott's brigades attacked, the British commander saw the US forces dressed in militia uniforms, and assumed he would have another easy victory. As the US line took losses and continued to attack in proper formation, the British commander took another look through his spyglass and is supposed to have remarked "Those are regulars, by God!"

However, the battle at Bladenburg showed the military efforts of the US were inadequate to stop the British Army. As the British Army advanced toward Washington, it was met by a hastily assembled US force, consisting mainly of militia. Most of the militia fled in disgrace, the only units to give a good account of themselves were a detachment of US Marines and the 5th Regiment of Maryland militia. The 5th Maryland advanced across open field in good order, temporarly forced the retreat of the opposing British unit, and quit the field of battle only when ordered to do so. This unit continued to perform its duty well, as after the burning of Washington, it was two privates from the 5th Maryland that killed the commander of the British forces invading Maryland. The British forces then retired from the inland excursion.

New Orleans is rightfully hailed as a militia style victory, but the battle occuring after the end of the war, tends to be discounted as a vindication of the militia system. The popular perception was that it was the regulars that provided the competence needed to sustain the military effort, with the performance of the militia considered of little value. This perception of regulars being the only effective force would influence US military thought fo the next century. This led to an increased emphasis on West Point (however adopting militia gray as the cadet uniform color) as a training ground for regular officers, building of coastal forts, and continued appropriations of $200,000 per year to arm the militia.

Later, over the objection of Secretary of War John C Calhoun, his plan for an expandable regular army was rejected, and the regulars were decreased to 8, and then 7 infantry regiments. The fact was that the best led and trained units, both regular and militia did well, and poorly led and trained units, both regular and militia did poorly. But, the image in the public mind of the militia fleeing the defense of Washington was a strong one.

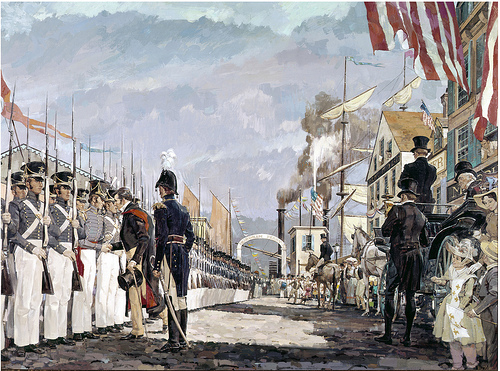

As a result of the war, national feeling was greatly enhanced, and a belief that the regular army and navy had won international respect for the ability of American arms. There was renewed interest in the militia, and new units founded, and especially in major cities, units become more serious about drill and uniforming themselves. The high point of this effort was during the 1824 to 1825 visit of Lafyette on his return and farewell to the United States. Militia units turned out to greet the hero of the Revolution. The 2nd Battalion, 11th New York Artillery paraded for him (pictured here) and adopted the name of Lafyette's command in France - "The National Guard".

As a result of the war, national feeling was greatly enhanced, and a belief that the regular army and navy had won international respect for the ability of American arms. There was renewed interest in the militia, and new units founded, and especially in major cities, units become more serious about drill and uniforming themselves. The high point of this effort was during the 1824 to 1825 visit of Lafyette on his return and farewell to the United States. Militia units turned out to greet the hero of the Revolution. The 2nd Battalion, 11th New York Artillery paraded for him (pictured here) and adopted the name of Lafyette's command in France - "The National Guard".

The Texas Revolution

Attention turned to westward expansion, and the tensions this caused with the natives. The regular army was increased back to 8 regiments of infantry, and a regiment of dragoons was added. The effects of the seminole Wars soon required adding another regiment of dragoons (now the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment) in 1836.

Meanwhile the regime of Santa Anna was increasingly intolerant of the civil liberties garenteed to citizens under the 1824 constitution (a result of independence from Spain). Tensions culminated in October of 1835 as Mexican troops demanded the return of a small cannon posessed by the citizens of Gonzales as part of the town's defense against Indian attack. The Mexican Army detachment was met by the Gonzales militia with the cannon loaded, and a flag picturing the cannon with the motto "Come and Take It". The Texas Revolution had begun, and news led to individuals and raising units from the US to join in the fight. The most famous of the units raised were the two companies of New Orleans Grays that set out for Texas immediately after citizens raised funds to buy the equipment needed from the local militia depot. Only one man survived from these units, the first company died at the Alamo, and the second died at Goliad. Another such unit was the Alabama Red Rovers, who also were shot after surrender at Goliad. When not overwhelmed by odds of 10 to 1 or greater, these citizens proved to be effective fighters. At one meeting where debate on the future course of action was considered, one man left the table and said "Who is going with old Ben Milam to San Antonio? His unit captured the city the next month.

This news bruoght Santa Anna north with his army in 1836. Taking the Alamo and Goliad led to settlers fleeing in panic in the "Runaway Scrape", while Texians attempted to rebuild a military force. These military disasters bought the time needed (with a little help from the US Army across the border in Louisiana) to pick a position from which to fight and defeat Santa Anna at San Jacinto. Texas was now an independent country.

The Mexican War

As it was obvious that this war would be prosecuted on foreign soil, Congress asked for volunteers for one year after declaring war, in order to avoid the Constitutional ambiguity that resulted in the War of 1812 over the issue of calling forth the militia for service outside of the territory of the states. While the state quotas were thusly filled from the militia, this resulted in the terms of service ending in 1847 while the Army was engaged in Mexico, and then having to request the men to volunteer again for the duration of the war. The Army usually fought battles heavily outnumbered, and while the regulars distinguished themselves, militia units fighting as volunteers also won fame for thier gallant conduct.

As it was obvious that this war would be prosecuted on foreign soil, Congress asked for volunteers for one year after declaring war, in order to avoid the Constitutional ambiguity that resulted in the War of 1812 over the issue of calling forth the militia for service outside of the territory of the states. While the state quotas were thusly filled from the militia, this resulted in the terms of service ending in 1847 while the Army was engaged in Mexico, and then having to request the men to volunteer again for the duration of the war. The Army usually fought battles heavily outnumbered, and while the regulars distinguished themselves, militia units fighting as volunteers also won fame for thier gallant conduct.

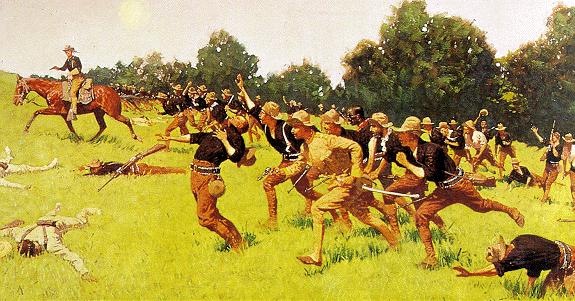

The most famous militia unit of the war was the "Mississippi Rifles" commanded by Col. Jefferson Davis. The actions of this regiment were key to the victory at Beuna Vista in conducting an attack, and repelling an attack of Mexican lancers, who stopped 80 yards away in order to draw a musket volley (which they knew to be ineffective at that range), and prepare for the physchological shock of a pointed lance charge. However, the rifles used the pause to take the opportunity to carefully aim their rifles, and decimate the lancers, who then fled in disorder. The small regular army, assisted by the volunteer regiments, was able to defeat Mexico in two years. This success led to the model to be used in subsequent wars of using the militia as a pool from which volunteer or expanded regular units could be created as needed.

The War Between the States

Both the North and South relied on the militias to fill the volunteer regiments after it became clear that a short term call up would not see the end of the war. Militia units volunteered as comapnies to be built into regiments, and larger units, such as the 7th Regiment, New York State Militia (formerly 2nd battalion 11th New York Artillery) volunteered as a regiment. "Silk stocking" units such as the 7th New York (pictured) or the Washington Artillery of New Orleans, in some cases had better equipment than the regular army - the militiaman pictured from the 7th New York, has a 1855 model rifled musket, which had not yet been issued to all of the regular army regiments by the start of the war.

Both the North and South relied on the militias to fill the volunteer regiments after it became clear that a short term call up would not see the end of the war. Militia units volunteered as comapnies to be built into regiments, and larger units, such as the 7th Regiment, New York State Militia (formerly 2nd battalion 11th New York Artillery) volunteered as a regiment. "Silk stocking" units such as the 7th New York (pictured) or the Washington Artillery of New Orleans, in some cases had better equipment than the regular army - the militiaman pictured from the 7th New York, has a 1855 model rifled musket, which had not yet been issued to all of the regular army regiments by the start of the war.

As the war continued, it was impossible to recruit for the regular army, and the regulars were withdrawn from combat in late 1863. Bonus payments were used by both sides to fill the volunteer regiments, and finally consription was resorted to in order to supply manpower. Thus the complaint that it was a rich man's war and a poor man's fight, as one could pay for a substitute if drafted. In a sense, this war represents a failure of the militia system, as neither side could obtain the required manpower via the militia system. The militia provided a refuge for those trying to avoid active service via the "home guard" units which were the militia units that did not volunteer for service and were in excess of a state's quota of regiments to be called forth. This was an especially effective tactic in those areas of a state that disagreed with government policy as to the war, with Union home guard militia units full of Confederate sympathisers, and Confederate home guard units full of Union men.

The post war period was marticularly hard on militia membership. The cost of the war made the public wary of military enterprises, while ex-Confederates were barred from militia membership. States segregated militia units based on race, and the reconstruction laws ended up disarming militias in the states of the former Confederacy. As a result, many units could not maintain membership, as citizens found reasons not to join militia units. While the veteran's organizations gained strength, many of those veterans saw their pre war militia units dissolved.

At this time another trend was heading in the opposite direction. Many of the state militias were banding together in the National Guard Association of the United States in order to lobby Congress for additional federal support of the militia. The primary goals of the organization were more federal funding and equipment distributions to the state militias.

Meanwhile, the regular army officers were impressed by the Prussian victory over the French in 1871. They saw a national army of conscripts with a basic military training who then were members of a reserve that could be mobilized to expand the standing army and fill out the active duty troops with additional manpower and units. This group advocated replacing the militia system with the German style military for the USA.

Congress debated over both proposals, but did nothing about them during the period of the Indian Wars.

The Spanish-American War

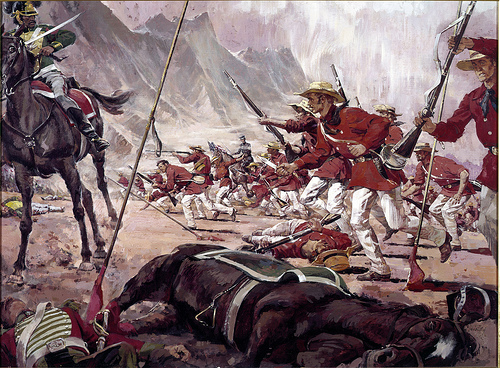

When the US declared war on Spain, the effects of neglecting the militia became well known. While the regulars had the .30 cal Krag bolt action rifle, the militia had the single shot breech loading Springfield. The militia (again soon to be volunteer regiments) were dressed in Indian wars blue uniforms, while the regulars had the new model khaki uniforms. The US Army was about to meet an army equipped with bolt action Muasers, and artillery firing modern smokeless powder, comapred to black powder 3 inch cannon of the US Army.

When the US declared war on Spain, the effects of neglecting the militia became well known. While the regulars had the .30 cal Krag bolt action rifle, the militia had the single shot breech loading Springfield. The militia (again soon to be volunteer regiments) were dressed in Indian wars blue uniforms, while the regulars had the new model khaki uniforms. The US Army was about to meet an army equipped with bolt action Muasers, and artillery firing modern smokeless powder, comapred to black powder 3 inch cannon of the US Army.

These organizational difficulties led to frustration and some took it upon themselves to organize and equip military units, such as the 1st US Volunteer Cavalry (Rough Riders) made famous via the coverage of their attack on San Juan hill in Cuba. Other more typical militia volunteer units found themselves outgunned and unable to defeat Spanish units without support from the regulars.

The results of volunteer performance, even to the point of recalling Civil War vets to duty, made the Secretary of War determined to reform the Army. This task would be made more difficult because volunteer units in the Philippines were needed to assist the regulars in the native insurrection.